Antarctica was, in a word, interminable.

The impossibly blue sky stretched on forever. The daylight never ceased, not even for an hour. The pure white terrain, rife with otherworldly shapes formed by the blistering wind, continued farther than the eye could see. But perhaps the continent’s vastest and cruelest aspect had nothing to do with its scenery. Rather, it was whatever clawed at the very sanity of its would-be travelers, obscuring every end but theirs.

At the center of it all were Barney Swan, 23, and his father, Robert Swan. The two men, united by blood and a singular mission to combat climate change, had resolved to complete the first-ever expedition to the South Pole powered solely by clean, renewable energy. The 600-mile, 60-day journey, started on November 22, 2017 and dubbed the South Pole Energy Challenge (SPEC), would prove perilous and debilitating, both mentally and physically. But the two of them, along with their team, were steadfast in their intent to make history and take one small step towards saving the planet — starting with some of the harshest territory on Earth.

This was Barney’s first real foray onto the world stage when it came to climate change, but Robert Swan had been a household name for decades among explorers and environmentalists. In 1989, he made history as the first person to walk to both the North and South poles, before being awarded the Polar Medal and appointed to the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Queen Elizabeth II. He was lauded by the United Nations with awards and ambassadorships. And in 2004, he officially launched 2041, a foundation named for the year the Antarctic Treaty will be renegotiated. Under the current terms, territorial claims and resource mining are prohibited. It preserves Antarctica for science and peace.

As Barney skied beside his father, towards the same location that had defined Robert’s legacy decades before, he realized he was reliving part of his father’s story — the one he’d heard in lecture halls and taxi cabs around the world. Antarctica stripped away all the banality of life, leaving only their bodies, their gear and their goal, all atop a far-reaching ice cap. On this journey, Barney felt he understood his father more deeply than he ever had: his folly, doubts, fears, ambitions, hopes and, overall, what drove him.

***

A ‘Pristine’ Laboratory

Robert and Barney’s mission is a noble one, scientists say, because Antarctica is such a fragile environment — one that is vital to our understanding of the world at large.

As far as potential negative effects from mining, Antarctica could be especially vulnerable.

“There’s just a greater risk of something going wrong,” says isotope biogeochemist Greg Michalski, who wasn’t previously aware of the moratorium year. “It’s very fragile down there. It’s such an extreme environment that what is down there has adapted to that extremity, so a rapid change is going to upset that ecosystem.”

Michalski, a professor of analytical chemistry at Purdue University, also pointed to the fact that the poles are warming much faster than the mid-latitudes of the tropics: “We’re basically transferring all the heat from down here up there.”

Dr. Andy Smith, a glaciologist at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), calls the continent a “unique, pristine laboratory” that’s the last — and best — chance we’ve got to understand the planet as a whole, the issues plaguing it and the best way to plan for the future.

Recently, the BAS shifted its focus to the Antarctic ice sheet after noticing it was melting faster than anywhere else — and faster than it had been in the past. They discovered the culprit was the warming of the ocean water in that region of west Antarctica. But there were many more links in the chain: Changes in the tropical Pacific were affecting weather patterns in that region of Antarctica. The weather changes were, in turn, affecting oceanic pressure distribution. And that change in pressure distribution presumably drove warmer water to the ice sheet and increased the rate of melting. It took decades to connect those dots, says Smith, and it drove home one point: The earth system is extremely complicated, and to shed light on any one area of the planet, it’s vital to study the entire system.

“In some ways, Antarctica is the only place we’ve got to understand the way the whole system works,” he says. “If we spoil Antarctica, then we throw away our chance of understanding all these things about the planet that do affect humanity.”

Potential knowledge isn’t the only thing at risk. If the ice sheets keep melting, islands in the Pacific could be submerged in as soon as 80 years, and areas of London and the U.S. East Coast could get uncomfortably close to more water. In fact, global warming of 34.7 degrees Fahrenheit by the year 2100 could mean a global mean sea level rise of anywhere from about 10 to 30 inches, according to a recent report by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

But nailing down the exact number of feet that sea levels could rise, Smith says, may not be as vital as understanding the ways in which minute increases could set off a sort of butterfly effect. According to the same scenario laid out in the IPCC report, an extra 0.9 degrees Fahrenheit of global warming — from 34.7 to 35.6 degrees Fahrenheit — could yield another 3.93 inches in global mean sea level rise. And that could expose up to 10 million more people to related risks. Small increases in sea level — even millimeters or centimeters — could worsen extreme storm events, not to mention impact the level of devastation caused by tornadoes, floods and other natural disasters.

***

The First Person To Walk to Both Poles

When Robert Swan was 11 years old, a technicolor film changed his life.

Called Scott of the Antarctic, the film depicted Robert Falcon Scott, a British Royal Navy officer and one of two explorers to engage in a 1911-1912 race to be the first person to reach the South Pole. The title would go to Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, while Scott and the rest of his team perished on the journey back.

The story struck a chord deep inside Robert, who believes to this day that “the last big dream, or the last big exploration, left on Earth is to survive on Earth.” He was drawn to the idea of proving to himself that he could survive the journey and also perhaps to the romanticism of what Scott represented. Indeed, Robert was born near the end of World War II, into a country steeped with damaged morale and restlessness, and his son believes that fueled the desire to do something so authentic — and, as Barney puts it, “completely mad, really.” At age 11, Robert cemented his dream in the form of a plan: Become the first person to walk to both the North and South poles.

That dream never left him. He went off to college, his mind consumed by the thought that Antarctica is the only place on Earth that is, essentially, owned by everyone and no one. (He was also delighted to find that his future plans as a polar explorer went over well with girls at parties.) After graduating at 22, Robert spent seven years raising the $5 million his dream expedition to the South Pole would cost. He worked as a taxi driver and a tree surgeon, presented his idea to potential backers, made fundraising calls and, eventually, put together a viable crew.

In November 1984, Robert and a small team set sail for the South Pole. After meeting the last surviving member of Scott’s 1912 expedition, the explorers spent the winter at McMurdo Station, a U.S. Antarctic research center on the edge of the continent, before setting forth on the 900-mile journey on foot. They didn’t have rescue airplanes, radio communications or GPS devices. On the 70-day journey to the pole, Robert lost almost one pound a day.

“We had to navigate 900 miles on foot to one building, the South Pole Scientific Station, in an area twice the size of Australia,” says Robert. “If we messed up with our navigation, I wouldn’t be speaking to you now.”

On Robert’s first expedition in Antarctica, the team trudged along underneath a hole in the ozone layer, and it felt as if “our eyes got burnt out [and] our faces got ripped off,” he says. He was shocked. He had thought someone else, perhaps government officials or scientific experts, sorted out environmental issues that could threaten the human race. He recalls thinking: Maybe these issues aren’t somebody else’s responsibility. Maybe they could be mine.

When Robert did make it to the South Pole on January 11, 1986, the moment was bittersweet. He received a call with million-dollar bad news.

Robert had bought a ship to carry his team to the edge of Antarctica, and it was stocked with all of the equipment they’d need to weather the winter before starting the spring expedition. His plan had been to pay off the $1.8 million debt he’d taken on preparing for the expedition by selling the ship upon the team’s safe return.

On the call, he was informed that minutes before he’d made it to the pole, the ship had unexpectedly sunk. An entire crew of people had needed rescue, and he was on the hook for millions of dollars.

It was time for a new plan: To get out of his sorry financial state, he would walk to the North Pole. The novelty of the idea — that Robert would be the first person to have ever walked to both poles — got people’s attention.

In 1987, Robert put together a team to trek across the frozen arctic ocean to the North Pole. But 600 miles in, he noticed the arctic ice cap melting beneath his feet. It was only April, four months before the ice was scheduled to melt. It was a historical first, and the team had no submarine standing by. It was life-or-death.

“We’re standing in the middle of the Arctic Ocean, 600 miles from the nearest land, and the entire bloody ocean melts beneath our feet,” says Robert. “We nearly died.”

Jeff Bonaldi is riveted by Robert’s story. He’s a friend of the family who has also partnered up with the Swans to send people on arctic expeditions via his own company, The Explorer’s Passage. “When he talks to me about it, it’s like the scariest moment of his entire life,” he says.

After escaping near-death circumstances, the team finally reached the North Pole on May 14, 1989. “It doesn’t mean anything to walk to both Poles — it’s completely pointless — but we were damn proud of what we’d done,” says Robert.

Robert is loathe to think of himself as an adventurer, environmentalist or activist. His first expedition, he says, had nothing to do with saving the planet or looking after Antarctica. He just wanted to get out there and do it without dying.

“Let’s get one thing straight: I’m not an explorer,” he says, naming figures like Scott, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen and American naval officer Richard Byrd as proper examples. “I’m too stupid to be a scientist. If anybody calls me an environmentalist, I’d like to slap them because I’m not. I’m certainly not an activist; I can’t stand the bloody word. You’re talking to somebody who’s damn good at staying alive. I’m a survivor… A good survivor does not see a perceived threat — like climate change, like ice caps melting beneath my feet at the North Pole, like increased ice breaking off Antarctica as NASA shows us — and do nothing about it. A survivor reacts to a threat before it gets them. So we are in the survival business.”

Upon his return, Robert met with Jacques Cousteau, one of his key patrons for both expeditions. The famed French explorer had stood behind Robert when no one knew or trusted him, helping fund both of his expeditions. Now, Cousteau wanted something in return: Robert’s commitment to a 50-year mission to protect Antarctica. It’s the only area left on Earth that everyone owns. In the year 2041, Cousteau told Robert, the treaty that protects Antarctica from drilling and mining could be altered or scrapped entirely.

That 50-year mission stuck with Robert. If the arctic ice cap melts entirely, it will surely set off a lasting environmental impact. But the Antarctic ice shelves warming enough to fall into the sea pose a much greater threat to sea levels rising, says Bonaldi, who calls Antarctica “Ground Zero in the fight against climate change.”

In the years after Robert launched the 2041 Foundation, he brought over 3,500 people from across the globe on more than 20 expeditions to Antarctica. His plan is to train young people as leaders so that when the time comes, he can call on them to help save the continent. He sailed 250,000 nautical miles to raise awareness about renewable energy and launched six education bases across India and the U.S. to educate young people about sustainable development. From 2010 to 2014, Robert spent four years bicycling more than 5,000 miles across India to educate students about sustainability and renewable energy. He says there are more young people in India than in the whole of Europe or the United States, and if they grow up to lead companies without adding sustainability to their agendas, the world will suffer.

“They would not remember some Englishman in a white suit in some bloody limousine,” he says of his decision to bicycle. “But they did respect the very red-faced Englishman on his bicycle arriving at their college, school or university. They will not forget it.”

But convincing people to care, especially on a wide scale, can be an uphill battle. “How do you save a continent on a 50-year mission,” he says, “when no one gives a shit about next week?”

***

‘Australian Rapscallion Youth’

Barney’s first glimpse of his father’s accomplishments, the sheer breadth of what he had been a part of, came at age seven, when Robert brought him to Antarctica for the first time. From then on, Barney was part of the world his father had loved for decades, and though they only saw each other a few times a year — Barney’s parents had divorced when he was three, and he lived with his mother — Robert took him skiing, mountain biking, rock climbing, hiking and camping. But above everything else, Robert’s goal was to teach his son to survive, to overcome anything nature could throw at him.

While Barney’s father taught him to conquer the outdoors, his mother taught him to respect it. Barney was raised off the grid in the middle of Queensland’s Daintree Rainforest, and it was there he learned to honor all living things, to stay curious, to listen to nature’s silence and to understand the fragility of any ecosystem. His mother’s hilltop home lay along a dirt road, kept company by nearby waterfalls and a number of free-spirited dogs and horses. The nearest convenience store was about 30 miles away. What the home lacked in electricity, it made up for with its abundance of color, of reading nooks, of cricket sounds. Sleeping there felt akin to sleeping under the stars.

The rest of Barney’s time was spent with his friends or, as he fondly puts it, “some Australian rapscallion youth.” His days were filled munching on vegetables, climbing pine trees, spearfishing, and doing so many doughnuts while driving that the car would catch on fire. He attended an Australian boarding school, but outside those walls, the ocean’s sheer power taught him one of his most enduring lessons: respect for the natural world and the power it wields over humans.

After that, Barney says a Catholic boys’ school “evened out” his forest tendencies and taught him how to conduct himself in a more structured environment. But he and his friends still spent much of their time outside, in the area where the Daintree Rainforest meets the beaches of the Great Barrier Reef.

***

The First Expedition To Run on Clean Energy

One day in 2016, Robert took Barney with him to visit NASA for the first time. He had friends there, and he wanted his son to experience the Silicon Valley facility. What he didn’t know was that Barney would leave that day with a newfound mission.

During their visit, a NASA team pulled up a map of Antarctica and pointed out the disintegrating ice shelves. They told Robert and Barney that one of the continent’s largest ice shelves, Larsen C — which is greater in size than the state of Maryland — would snap off soon.

“This is happening now — more than even the most pessimistic scientists thought it would — and if we let it just disintegrate… we’re swimming,” Robert remembers hearing.

In fact, the ice shelf did break off in 2017. And though a floating ice shelf atop the water won’t directly impact global sea levels, the break could mean that glaciers from the land behind the ice shelf could flow into the ocean. Those events would cause a rise in global sea levels.

He says the NASA team wondered why no one was taking their findings seriously. Robert replied that it was because they were presenting the research in an uninteresting way, and he resolved to do more on his own end to increase support for renewable energy.

Barney had a different take. He was inspired, impassioned, resolute. “We’ve got to get out there, and we’ve got to do something,” Robert remembers his son saying. It wasn’t long before Barney came up with the idea for the South Pole Energy Challenge.

Training required a multifaceted approach — preparing for a significant increase in altitude, and therefore, a significant drop in readily available oxygen; for dragging sleds behind their skis for hours on end; and for conditions so harsh that simply surviving in them burned 6,000 to 8,000 calories a day. Barney and Robert prepared with methods like dragging tires up hills with trekking poles and alpine hiking with rocks in their bags.

One of Barney’s childhood friends, Daniel D’Hotman, planned to ski only the last degree of latitude (equal to about 69 miles) with them, but his training still required spending four to six hours every Sunday wearing a 65- to 90-pound weighted backpack, carrying walking poles to mirror the ski poles he’d depend on in Antarctica and dragging tires around dirt tracks. He took on yoga, weight-training and six- to nine-mile runs a few times a week, as well as stints at an altitude center and with cross-country skiing coaches.

The nature of the Swans’ mission required even more intensive training than usual. The clean energy technologies they planned to bring along would make their load heavier than that of a “typical” expedition, which would be largely powered by jet aviation fuel. The Swans’ materials list included portable solar technology lithium batteries to charge cameras, biofuels made from wood chips and algae and a solar-powered ice-melting system developed by NASA. The extra time and energy needed to move those supplies would prove dangerous — both in terms of physical stamina and the loss of valuable time that could otherwise be dedicated to eating or sleeping.

Beyond physical strengthening, mental preparation is key. Preparing yourself for the endless white — the lack of color, the sameness stretching in all directions — can be exceedingly difficult, says Barney.

Weeks into their journey, that whiteness surrounded Barney as he skied beside his father. They pulled sleds that started at over 220 pounds. It was difficult for Barney to wrap his head around the absence of leaves, hills, insects, sand and rocks — there was only ice.

And that ice was brutal on the body.

Harnesses used to drag the heavy gear resulted in torso pain, leg chafing led to bleeding, the ski sticks meant sore hands and frostbite was a constant concern — especially for Barney, who got it on his face, fingers and toes. As the days bore on, Barney saw his father retreat further into himself the farther behind he fell. Plagued by the memories of friends who had perished in Antarctica, Robert knew that if he’d fallen too far behind on the same journey more than 30 years before, he would’ve been left for dead.

***

Not Even ‘the Terminator’ Could Take It Anymore

The team was running out of food.

The more they slowed their pace, the lengthier the duration of the trip. And try as he might, eventually Robert — and his faulty hip — couldn’t keep up. He felt like the Treasure Island character Long John Silver, who hobbled on a peg leg. The pain consumed him.

About 31 miles shy of the halfway point, he skied up to his son. “Do you feel like you three can get to the South Pole?” Barney remembers his father asking. It was followed by a painful admission: Robert didn’t believe he could make it, especially in the time allotted by their food supply. “After 300 nautical miles, not even the Terminator, which Barney calls me, could take it anymore,” says Robert.

They made the final decision together. Robert would turn back, and Barney would continue.

It was the hardest decision of Robert’s life.

“I know the Antarctic pretty damn well, and Barney was about to go into the jaws of death,” he says. “I said to him, ‘Barney, you are my son. You can do this.’”

Barney remembers his father warning him to take care of himself — that if Barney’s frostbite spread and he had to make the call to leave, there was no shame in that.

Despite his advice, Robert felt that by turning back, he’d failed both his son and the expedition.

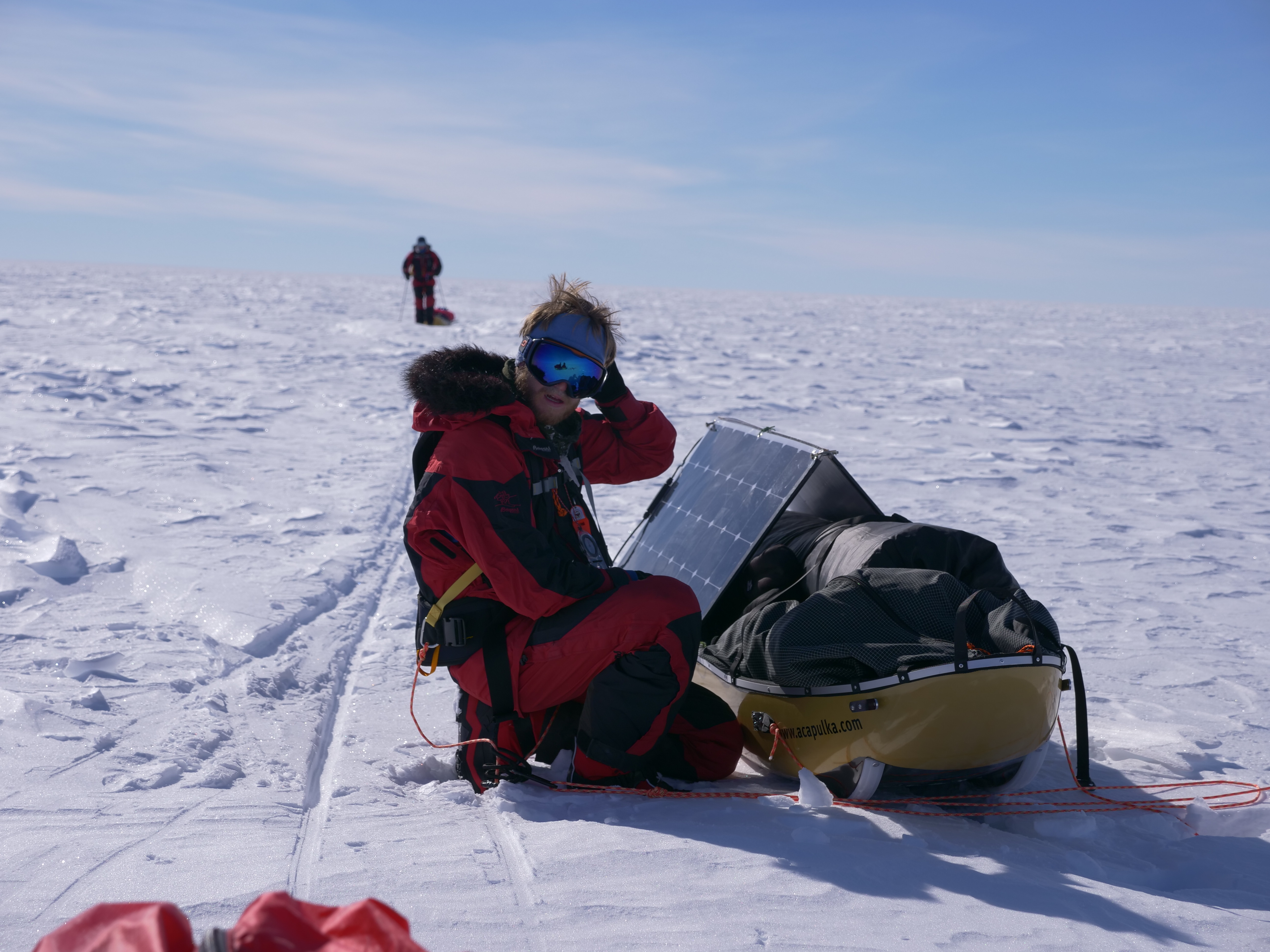

The team made it to the halfway point, a spot with a standalone bathroom, emergency supplies and airplane fuel containers in the Ellsworth region’s Thiel Mountains. Using a satellite phone charged with solar panels, the team called a Twin Otter plane to pick Robert up and bring him back to where they started: Union Glacier Camp, below the region’s Ellsworth Mountains.

Before Robert boarded the plane, Barney remembers his father’s final words were a call to action and an instruction to take the journey one step at a time.

“My blood runs through your blood,” Robert told him.

***

‘When Does This Become a Fucking Serious Thing?’

The wind seemed to blow more quietly in Robert’s absence. For days, Barney was accompanied by a near-constant mirage of his father skiing behind them, coming up over the horizon.

The weight of what lay ahead and the speed at which they needed to move to stay alive plagued the team. They pulled their sleds away from the mountains and back into the bleak white landscape, surrounded by the same view of ice in every direction.

On day 45, in negative 49 degrees Fahrenheit, Barney’s inner thighs were chafing and bloody with bits of flesh coming off. Parts of his toes were black, and the odor was repulsive. Despite the stubborn frostbite, he knew he had to put his boots back on and walk another eight hours the following morning. His feet were completely numb for two days.

Barney and the two young men skiing alongside him, Kyle O’Donoghue and Martin Barnett, switched off between a two-person tent and a solo one, and on every third night, it was Barney’s turn to sleep in the latter — the “bachelor pad.” After discovering his frostbite had worsened, Barney visited his friends in the other tent to gauge their opinions.

“Guys,” Barney remembers asking while he showed them his toes, “when does this become a fucking serious thing?”

His friends’ faces fell.

As his frostbite worsened, Barney’s decisions became more dire and far-removed from the types he’d had to make in his everyday life in Australia. He had to find the middle ground between damaging his toes and losing them altogether.

During some of the most difficult moments — like when he couldn’t remove his socks for fear of removing more bits of flesh along with them — Barney knew there was no real question, at least in his own mind, of abandoning the mission. He knew that if he pulled out of the expedition for any reason, the change and public awareness he hoped to receive would look much different. He knew he was in his current situation by choice, and he couldn’t stop thinking of the mountain of others across the world, in extreme poverty, in mourning, in pain, who hadn’t chosen their current circumstances and had no eject button.Stop fucking complaining, Barney told himself. You’re in this situation by choice. You have freedom.

So he soldiered on, accompanied by his two fellow explorers, hundreds of pounds of gear and raw, unadulterated thoughts. And somewhere amidst the endless white, Barney dubbed himself an optimistic nihilist. Stripped of the normalities of life, he’d concluded that humans are parasites, consuming ourselves into oblivion. On the other hand, he thought, there’s real power in action, ethical business and positive role models. He resolved to be someone who contributed less to the damage and more to the cleanup. Since everything hurts the planet in one way or another — purchasing jeans, hopping in a taxi, buying a plastic bottle — Barney resolved to help distribute that complacency.

One day, Barney looked up to find a circular rainbow directly above him in the sky. The sun evoked a fiery halo, and its light passed through the sides of the rainbow to meet at some point behind him. In the past, he’d laid eyes on the Northern Lights and the glow of bioluminescent phytoplankton in the ocean, and he found this sight just as awe-inspiring. The team decided to camp underneath the spectacle, and Barney sat outside underneath it for a while. Later, he fell asleep while visualizing it above his tent. He could almost hear it, he says, and he could definitely feel it.

It felt hopeful.

***

A Silvery Sphere on Top of a Red and White Pole

The South Pole is marked by a red-and-white-striped pole topped by a silvery sphere. It’s circled by the flags of the 12 nations that signed the original Antarctic Treaty in 1959, and on day 58 of Barney’s expedition, the sphere reflected him, O’Donoghue and Barnett as they finally achieved their goal.

The three celebrated. Exhausted, with frostbitten feet yet flooded with relief, Barney kissed the South Pole. Then, for the first time in months, he saw his reflection, bearded and slightly frostbitten, in the Pole’s sphere.

The team had emerged from what felt like sheer nothingness to an area with marks of civilization. After almost two months, they had made it to the place they’d dreamed about. But after the initial excitement, they were amused to find that reaching the Pole was a bit anticlimactic.

Robert and a group of other adventurers including D’Hotman had flown to a spot one degree from the Pole, and at mid-afternoon one day, they saw the figures of Barney, O’Donoghue and Barnett in the distance.

Once the entire group was united at the Pole, D’Hotman noticed Barney had gained a beard and lost more than 10 pounds — and after having traveled with his friend across five of the seven continents, D’Hotman was elated to see Barney in what he calls the most amazing natural environment on Earth. Barney says it wasn’t until he saw his loved ones there that he felt that the expedition was over.

When Robert skied up to the Pole for the first time in over three decades and saw his son there, having successfully made history, his eyes brimmed with emotion. They lay down next to each other in the snow and talked of how this expedition connected to Scott’s journey over a hundred years before. There was silence filled with love and pride. And as they lay there, the world seemed to stand still — partly because they were on its spinning point.

“There was a lot of hugging and maybe a few tears shed,” says D’Hotman.

The entire brigade retired to a small tent for a three-course meal. There was salmon, avocado, chicken, mashed potatoes, beer, wine and, best of all, a heater. The following day, the team visited McMurdo Station’s greenhouse at the South Pole, and Barney, an avid gardener, laid eyes on greens and soil for the first time in months. He considers that moment the best smell he’s ever experienced.

***

The Bravest Thing To Do

In the following months, Barney took 29 planes — to Brazil, London, Vietnam, Dubai, Florida, Seattle, Chicago, Australia — to spread the word about 2041’s mission. And in February 2018, Robert and Barney traveled to the southernmost tip of South America, nicknamed the “End of the World,” to board a ship called the Ocean Endeavor that would take them back to Antarctica.

This trip, by boat, would be infinitely less taxing, and accompanying them were 90 other travelers from more than 20 nations. The purpose of the expedition: Bring tomorrow’s leaders in business, banking, environmental advocacy and more to the austere continent so they could experience firsthand the reason it should be protected forever.

There’s an intrinsic magic to seeing Antarctica with your own two eyes, says Anjuli Pandit, program director for 2041’s Arctic expeditions. She says it eliminates everything — your age, your career, the labels you bear as a daughter, husband, neighbor, voter — and you never come back quite the same.

The trip was to be all that and more, but though Robert was there physically, his mind seemed to be someplace far away. Pandit believes he was still stuck at the 300-mile-mark in the South Pole, the point at which he turned back, and that he wasn’t quite sure how to be around others after what he considered a complete and utter failure. He spent a lot of time alone, so Barney, who was still recovering from frostbitten toes, took the lead in getting to know the travelers. Pandit recalls seeing Barney look people in the eye on the boat and say, “You’re coming with me to the Antarctic” — and more often than not, they would. “He has that ability,” she says.

One evening, Barney told the travelers the story of his harrowing journey to the South Pole. He talked of his frostbite, fits of minor insanity, sleeping bags that stank of urine and, finally, of pride. During his recounting, he showed a photo of his father backed by a white expanse of snow. Robert looked like he’d seen a ghost, recalls Pandit. His eyes were full of intense fear, and though he stared into the camera, his gaze seemed to go right through it.

“Have you ever seen your father or mother look like this?” Pandit remembers Barney asking the group. “I can’t tell you what it was like to watch my father literally die in front of my eyes, break down who he was and go into that place… For my father to make the decision to turn back — it’s the bravest thing he’s ever done. For him, quitting is an immensely brave thing to do.”

Pandit recalls Barney saying that his father’s bravery made him stronger, as both a son and a human being. It was the catalyst in his becoming a man. And because he was given the opportunity to accomplish something himself, he would never have to live in anyone’s shadow.

“After that, Rob was back,” says Pandit. She remembers seeing him smiling from ear to ear and growing chattier every day. On the last day, Robert apologized to the group for essentially being absent during the first 10 days, saying it had been the hardest experience of his life. He had been consumed by the idea he’d failed his son and the expedition, but after Barney spoke, Robert saw the experience differently.

“[I] gradually realized that actually, this was the best thing that could have possibly happened because it gave Barney that chance to be himself,” says Robert. “Not under my shadow, but himself — his own story, nothing to do with me.”

***

Taking Up the Mantle Beyond Antarctica

With his father’s blessing, Barney is building his own legacy.

He and the 2041 team are working to evolve the organization from its first iteration, what Robert ran for about 20 years, into something new. The two visions will be unified under one strategy: the ClimateForce campaign.

The next major goal Barney hopes to accomplish through ClimateForce is a tall order: Clean up 360 million tons of carbon dioxide over the next six years. He’s got a list of concrete strategies to get there. He and D’Hotman, who serves as ClimateForce’s director, are researching evidence-based investing in order to choose the most effective environmental charities to support and aiming to finalize the portfolio by 2025. They’re also hard at work building a web tool and app to “gamify” carbon dioxide cleanup, allowing consumers to choose ways to help advance the 360 million-ton cleanup goal with just one click. One $1 donation, for example, sponsors the cleanup of one ton of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. (A tree would need to grow for 40 years to make that happen, according to 2041.)

Barney also wants to focus on funding education programs that utilize new tech to inspire the next generation of leaders. He and D’Hotman are focusing in on virtual reality to show everyone from schoolchildren to CEOs what it’s like to visit Antarctica, the Amazon rainforest and a number of oceans, and Barney says he’s already showcasing the technology. They believe a connection to the environment, fostered by way of experiencing it — or feeling as if you’re experiencing it — firsthand, is the most accessible way to motivate people from every subset of life to offset the effects of climate change.

Then there’s the up-close-and-personal adventure aspect of the organization — fostering in-person experiences for high-impact leaders in business, policy or philanthropy to inspire them to take up the mantle in the fight against climate change. So far, 3,500 individuals, reportedly from upwards of 90 nations, have traveled with 2041. Together with Bonaldi, the Swans have launched a strategic expedition series to the most at-risk areas around the globe when it comes to the effects of climate change. The Explorer’s Passage and 2041 will partner to bring a group of travelers to the Arctic in June 2019, and three months later, another group will plant one million trees around the base of Mount Kilimanjaro as part of a new carbon-negative initiative. The organization acknowledges that most forms of travel aren’t environmentally friendly, so they’re pursuing this initiative to offset the carbon footprint they rack up during the expeditions.

Making young people better leaders is how Robert’s legacy fits into 2041’s new look. “If you make better leaders, then those leaders are going to become more influential,” says Robert. “They’re going to be powerful women and men… If they get this feeling that we should preserve Antarctica, which we show them, I can ring them up in 23 years and say, ‘Right. It’s action time. Let’s get on with it. Let’s save Antarctica.’”

The other aspect of the solution, of course, is making the goal financially attractive to big businesses. Using more clean, renewable energy in the real world will drive down the cost of alternative fuels, meaning that in 22 years, no one would need to go to Antarctica to exploit it, says Robert. Hopefully by that time, it won’t make financial sense. “Add three things together: Nobody owns it, you’ve got a fleet of incredibly powerful people ready to attack in 2041 and it doesn’t make financial sense to [exploit] it, we have a chance,” says Robert.

Robert is nothing if not a survivor, and in that vein, he has another adventure in the works. He made his way over 900 miles of Antarctica 22 years ago, and with Barney, he crossed another 600 miles. But Robert still sees himself as being 300 miles short of his goal. And, true to form, he’s not giving up.

“I’ve always had this dream ever since I was 11 that one day I would have crossed the whole continent of Antarctica,” he says. “I now have a new hip, and at the end of 2019, I am going back to exactly where I said goodbye to Barney, and I will complete those last 300 miles to the South Geographic Pole at the age of 63, which is far too old to be doing this sort of thing, but who cares? It will have taken me 35 years, which I quite like, to have crossed the entire Antarctic continent.”

Barney says he thinks his father is “mad” for attempting the journey again, but he respects him wanting to finish it. And when Robert nears the Pole, Barney will travel there to cross the last degree (about 60 nautical miles) with him. “The roles will be reversed,” says Barney. “It will be surreal to say the least.”

On the expedition, Robert plans to test out materials that allow consumers to “feel, touch and use” solutions to the ever-growing carbon dioxide emissions problem. He’ll bring backpacks made of recycled plastic, smartphone cases made of atmospheric carbon dioxide with solar panels attached and more.

“Barney is everything I should be. Barney is everything that people think I am,” says Robert. “Barney and I are very different people… But we don’t bloody give up. If there’s one thing that joins Barney and Robert Swan, it’s that we don’t quit.”

***